The Basement Band (1997-1998)

Let’s get in the Way-Back Mobile and go back to maybe 1997 or ’98. I was home from college for a few weeks, and my dad was working as head of HR for a plastics company just outside Pittsburgh. One of the employees was retiring, and they were throwing a party. Somehow it came up that my dad was a drummer, and they asked him to play a few tunes at the event. He laughed it off and said no, it had been too long since he’d played.

But I was home, and I told him, “We can do it. I’ll get Dan to play bass, and I’ll play guitar.”

We rehearsed in my parents’ basement, with a cold concrete floor, an unfinished ceiling, and the smell of laundry hanging in the air. The set list was simple: Louie Louie, La Bamba, and… something else I can’t remember, which probably means it wasn’t worth remembering.

We practiced every night for the time I was home, long enough for my dad to shake off some rust and find his old swing again. I can still see him holding the sticks with that traditional grip, rocking back and forth, keeping the beat, remembering the fills that used to come second nature.

And through it all, my mom somehow tolerated the noise. My guitar blaring, Dan’s bass rattling the heating vents, Dad’s drums echoing up through the floorboards, she never once told us to stop. I have no idea how she managed it.

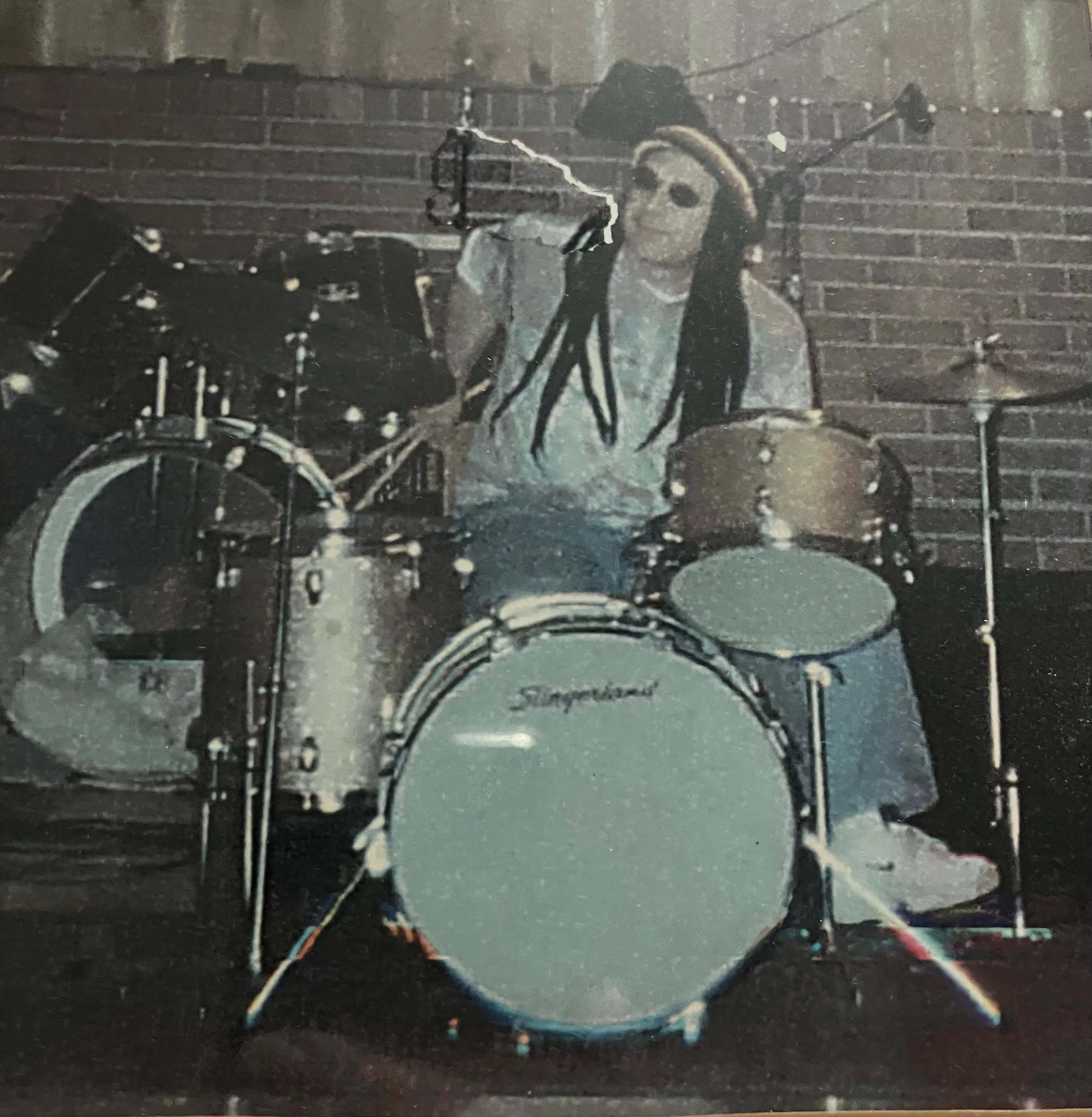

A Rastafarian Hat and Dreadlocks

When the night of the party came, the band playing at the event was really good, professional-level good. But they were kind enough to let us jump up during their break for a few songs. We set up and played our three-song set, and it was pure chaos in the best way.

I had bought my dad a Rastafarian hat with fake dreadlocks and a pair of sunglasses for the show. He added a tie-dyed shirt to complete the look. It was absolutely hilarious and so out of character. This was the same guy who, every week for 30 years, wore brown on Tuesday, gray on Wednesday, and blue on Thursday, following a schedule like clockwork. But that night, he let go.

It was the first time I ever saw him let go. Not as my dad, but as a person, laughing, playing, entirely in the moment.

Growing up, he was steady and distant in the same breath, the man who went to work, came home, ate dinner, watched the news, showered, and went to bed. Reliable. Predictable. Unreachable. But that week, something shifted. Down there in the basement, with the amps humming and the floor shaking, we weren’t father and son anymore. We were bandmates, equals in the noise, sharing the same rhythm, maybe even communicating in the same language.

The Moment That Stuck

I’ll never forget how, while we were up there playing, the singer and guitarist from the real band that evening stood in the crowd watching us. I don’t know who he was, or even remember the band’s name, but I can still picture his face.

He kept looking at me, nodding, smiling, motioning for me to keep going, and encouraging me to play and sing. That look of encouragement, that silent “you got this,” meant so much.

It was a small gesture, but it meant everything. He didn’t have to do it. We were just a novelty act at a retirement party, a father, a son, and a friend fumbling through a few songs. But in that second, it felt like he was handing me something invisible, permission to believe I belonged up there.

I wish I could find him now, shake his hand, and tell him how much that meant. I’ve never forgotten that moment.

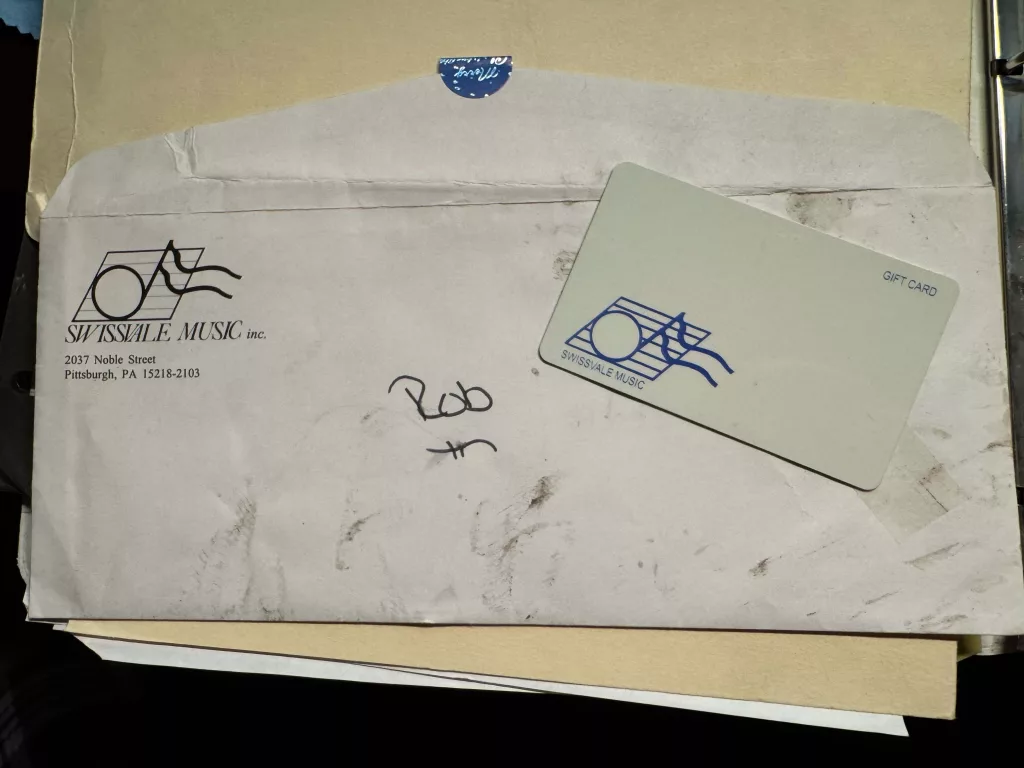

A few weeks later, after I went back to school, I got an envelope in the mail. My sister’s handwriting was on the front, but inside was a gift card to Swissvale Music from my dad.

No note. No message. Just the card.

But I didn’t need words. That was his way of saying what he couldn’t say out loud. It was the first musical nod I’d ever gotten from him, maybe the first real nod of any kind.

Somehow, it felt like the invisible line between us, the one that had always been there, had shifted just enough for music to pass through. I kept that envelope and card. I still have it today.

Borrowed Beats (2019)

Fast forward twenty years.

The stars aligned, and we had a jam session planned. No P.I.B.E., no anxiety, but hauling a full drum kit across town for one night felt like overkill. So I called my dad.

He still had that old 1968 Slingerland kit, in its gorgeous champagne sparkle finish with a chrome Gene Krupa snare. It had been sitting in the same bedroom closet at my parents’ house for years. It was one of his pride-and-joy possessions, and as a kid, I wasn’t allowed near it. I couldn’t even breathe on it.

No way I thought he’d lend it to me, but I asked anyway.

Frankly, I was stunned. He didn’t hesitate; he just told me to “take care of it.”

That Surreal Moment

When I first unpacked it to start seting it up, it still had the original drum heads, worn in, yellowed, soft around the edges, like a cool old leather jacket that’s been broken in just right. Tom played on those original heads that night, and the kit sounded incredible, full of history and warmth, the kind of tone that feels like it has something to say.

Afterward, when I called my dad about returning them, he told me to keep the drums. I almost fell over.

That’s when I took them to Main Street Music to have them freshened up. Paul, who’s been there since the old Swissvale Music days, took one look at the Slingerlands and smiled like he was seeing an old friend.

He’s a drummer himself , the kind of guy who knows exactly what a kit needs just by the way the shell resonates. He swapped out the batter and resonant heads, gave them a careful tune-up, and handed them back to me sounding better than ever.

The warmth that came out of those shells was unreal, not the sharp, bright crack of a modern kit, but a deep, rounded tone that felt alive.

It made me wonder if those old Slingerland shells were holding on to something , a secret tucked inside the wood from all those years of music and silence.

A Pandemic, and a Pulse

Then 2020 hit, and the world just… stopped. Work paused, life paused, and suddenly those Slingerlands were still sitting there, gleaming in the corner.

One day, I sat down behind them and started playing. Badly. Uncoordinated. I’d work on one drum at a time, kick, snare, floor tom, trying to figure out how it all fit together.

Little by little, I found a pocket. I could keep a beat, hold a groove. I learned how to tune the drums, how different heads changed the sound, how a small adjustment could make them sing or choke. Those hours became my therapy, a mix of rhythm, sweat, and escape.

My daughters got in on it, too. After dinner, they’d take turns banging away, laughing and fighting over who got to hit the crash cymbal next. It was noisy, chaotic, and perfect.

The house that once felt too quiet during lockdown suddenly had a heartbeat again.

Whenever my dad comes over now, he always makes a beeline for the kit. He’ll sit down, grab the sticks, and start playing, rocking back and forth like he never stopped. A little Gene Krupa, a little Buddy Rich, a lot of Cozy Cole‘s Topsy Part II. It’s all still in his hands, just a little rusty.

One time, I hit record while he played, to capture it. He had no idea. Later, when I listened back, it hit me how much that sound meant.

It wasn’t just drums.

It was memory, connection, and time collapsing in the best possible way.

We still use that Slingerland kit for our jams a few times a year. Every time Tom sits behind it, or my dad drops in for a few fills, it feels like the music keeps looping back around, the same rhythm, the same story, passed from one pair of hands to another. A lot of the drum sounds on the album (if you want to call it that) “Spacejunk” I created during Covid was on those drums. They’re pretty prominent on “Charlie W.“

The Kit That Remembers

That 1968 Slingerland kit isn’t borrowed anymore. It’s part of my story now, mine for a while, and someday, my daughters’.

I’ve come to think instruments hold a little of everyone who’s ever played them. They don’t just make sound, they remember. They’re imprinted. Every note, every scratch, every worn patch tells part of the story. Some sounds fade, but some seem to linger, waiting for someone new to pick up where the last person left off.